Lightkeeper of Currituck | Roulez Magazine

July 12, 2020Meghan Agresto is a modern day lightkeeper. She and her two sons, Benicio and Paolo, several chickens and the family dog Jess live on Currituck Beach Lighthouse grounds where she manages operations for this popular and historic attraction of the Outer Banks.

Located in Corolla Village at the northern end of the Outer Banks, Currituck Light was constructed in the 1870s to fill the void of light along coastline stretching 40 miles between Cape Henry light and Bodie Island. The lighthouse’s beacon can be seen for 18 miles and even today helps ships navigate through tricky waters where many vessels and lives have been lost.

The grounds around the light include several historic structures. Of particular interest is the original lightkeepers’ house. This Victorian stick-style building was completed in 1876 and provides an excellent example of architecture of that era.

Here, two keepers and their families lived in duplex arrangements with the light located only steps from their front doors. Otherwise, the setting of that period was completely isolated. There were no neighbors, socialization or general outings to be enjoyed, beyond a boat trip to the mainland for supplies or other needs.

Originally run on lard, then kerosene, the light became electrically operated in the 1930’s. This greatly reduced the amount of labor required to maintain light operation and keepers themselves became somewhat obsolete.

Because of the staff reduction following that innovation, much of the property stood in disrepair by the 1970’s. It was in 1980 that a group called the Outer Banks Conservationists signed an agreement with the State of North Carolina to restore the property to its original quality and to ensure generations of visitors could experience a glimpse into true Victorian lighthouse lifestyle.

Convergence of Today and Yesteryear

It was about ten years ago that Meghan Agresto stepped onto the property as the new lightkeeper of Currituck. Her son Benicio was then just under a year old. Paolo arrived later, the city slicker of the family.

“I want to live in New York City,” eight year old Paolo claims.

Benicio, now eleven and in sixth grade, seems to love his life in Corolla. “I like the beach and the weather – it’s not too hot and not too cold. I like the privacy and how there’s not that many people here,” he says.

Both boys are energetic and social. Dog Jess is a happy dog. The boys laugh, romp and play on the grounds while their mother sits on a bench, discussing their lives and what brought them here. It is a healthy lifestyle, one reminiscent of days gone by.

“Living up here we don’t have exposure to as many things,” Meghan explains. “But living in a city, we could be in more of a Helicopter Mom nightmare. Here it is more like living in the 1980’s.”

The children seem to appreciate what they have at their feet, living in Corolla.

Meghan continues, “We do some things we might do if we lived in a city. We take swim lessons. We have a casual swim team. So we’re not completely isolated. We do see the ‘real world’ in the summertime, when we get to meet visitors who have non-service industry jobs.”

Meghan is referring to Corolla’s primary existence as a summertime resort for visitors from all over the United States. During the winter months, Corolla is quiet and empty. In summer the village swells with the vibrant beach resort lifestyle most visitors believe exists only between June and September.

Despite being in a quiet retreat and living in a bit of social isolation during the winter months, Meghan is a worldly soul. She has lived in nearby Chapel Hill, Washington DC, New Mexico and as far away as Spain, Greece and elsewhere. The lightkeeper lives and works on a quiet compound just south of some the country’s most isolated beaches. But she is well-traveled and highly educated. These are attributes which likely provide the foundation for her sons’ naturally pleasant social demeanor around visitors to their designated home.

“I grew up everywhere. I come from an academic household. My mom worked in the National Laboratory in Los Alamos and my dad was president of a college there.”

Meghan is a charming, outgoing, friendly lady with positive energy and genuine interest in the people around her. She asks many questions, the type of questions meant to strengthen even a temporary bond. She is warm and makes you feel welcome, as if you are as much the interviewee as the interviewer. Spending time with her is a dialogue, never a monologue.

Meghan is able to relay history of the lighthouse and Outer Banks in an interesting, thought-provoking manner. She knows the political nuances of historic lightkeepers’ lives and how they related to their superiors and each other. Her knowledge of the social side of lightkeeper life, architecture of the structures, history and other aspects of her realm is deep, generated by hours of research and review of archival documents. Benicio is seemingly in her footsteps, able to name individual lightkeepers upon hearing of their personality quirks or personnel file notes mentioned in passing by his mother.

As we ambled down a short trail to the family home, I had a passing thought of the iconic 1980’s film The Goonies, wherein a group of boys and girls band together to save their homes from impending demolition. They end up embarking on a pirate adventure complete with treasure and criminals in pursuit. Here, such a story almost seems likely. In my mind’s eye I can picture these boys, their dog Jess and a few of the chickens tearing off across the lawn of the lighthouse, out to the beach and in search of pirate treasure lost to shipwreck so many years ago.

A Beacon of Island Education

When there is a problem, Meghan is the type of person who works to intelligently solve it. Such is the case with education of area children. Much like lightkeepers of the Victorian era, the enterprising mother was faced with how to educate her children without doing as locals had to do at the time of her arrival: sending them on a bus to another county every day.

Meghan explains, “Part of my job description is that I have to live on site. When I moved here I had my older son, Benicio. He was just under a year old. I realized that everyone moves south to Dare County when their child is about five years old, so the kids can go to school.”

“I thought, ‘Well everybody here tends to have a kid and then moves away. That can’t be me. I don’t want to quit my job. I love my job. You see how great my life is. I can’t quit this job.’”

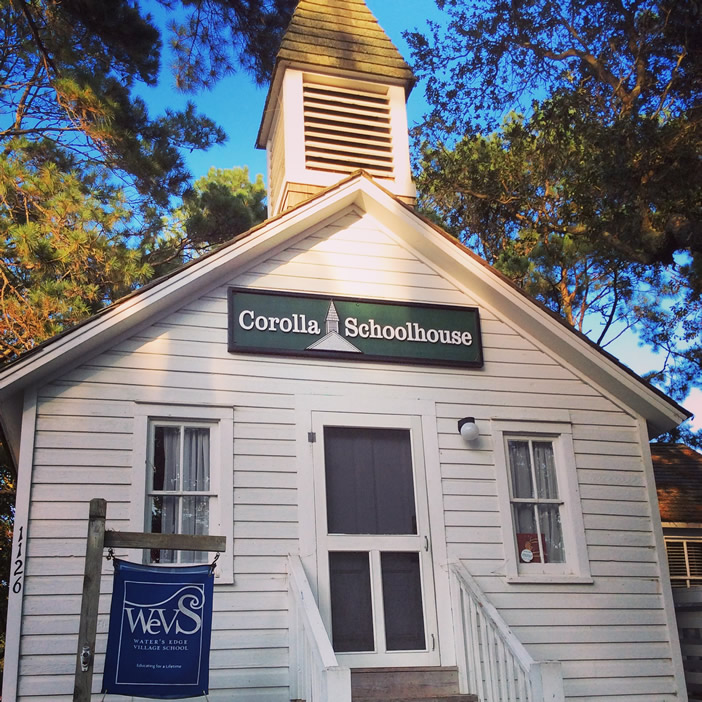

Only yards away from the lighthouse, a school was built in the 1890s by the lightkeepers with permission of the U.S. government. It was for the keepers’ children’s education. From the early 1900s to 1958 it was a Currituck County school. By 1955 there were only five children in the academic setting and in 1958 the school closed. Children then had to be ‘shipped out’ to go to school in Dare county or elsewhere. The building became a private residence for awhile, at times an office and had been used for other commercial purposes.

Meghan said, “I went to a high school whose motto was, ‘Find a way or make one.’ That is how I live.”

“I want to be here. I want my kids to have great options here, where they live. I didn’t want them being picked up by a bus at 630am, driving so far for a 9am school time. I realized I cannot have my child gone for 12 hours per day for a six hour school day.”

She continued, “So I talked to a woman I know, Sylvia, who is now our teacher. We worked together and formed a nonprofit, put together a board and started figuring out what we needed to do to start a school. First we looked into churches and other potential sponsoring organizations, then into maybe getting a big donor and forming a private school. But then we learned about charter schools. So we applied to the state of North Carolina and they turned us down. We reapplied the next year and were granted a ten-year charter.”

“I managed the deadlines and laws, Sylvia managed and developed the curriculum.”

Now, the Corolla Schoolhouse is a school again as it should be, under the name of Water’s Edge Village School. This year it is the education center for 27 students with their own yearbook, two classrooms, two teachers, multiple teachers’ assistants and a well-developed curriculum any school would be proud to present to the public.

All of this is housed within a charming wood structure one would expect to be existent only in storybooks. Classrooms are colorful, cheerful environments of yellow and whitewash. It is the kind of school where kids form relationships which last for a lifetime.

The school and its surroundings are a scientific or creative minds’ idyllic setting for development and education. Kindergarten to sixth grade are presently served by this little educational-institution-that-could.

Meghan proudly asserts, “We don’t have a soccer team. Some people see that as a problem. But our kids do get to go kayaking, they get to go surfing, they get to go kite boarding. This is such a great place to be educated. There’s the business side of life here, the outdoors, the ocean, wild horses. We think about the whole village as our extended campus. We might go to the park, beach, the top of the lighthouse, resort swimming pool or wildlife center. It is a non-traditional approach, but that is my way anyway.”

While the school is very small, it doesn’t lack for technology. They have smart boards, projector setups and access to whatever the kids need for their classroom time. In fact, they have more community support than many schools with much larger facilities.

Once per week, local restaurant Corolla Pizza donates pizza to the kids for lunch. Otherwise, each student brings their own lunch and everyone eats in the classroom.

“There are a lot of retirees here in Corolla. So they have really embraced the authenticity of having kids around, instead of having the kids leave to go to school. They love the vibrancy the kids bring to the community, so we get a lot of volunteers,” Meghan explains, her appreciation showing. “We have a weekly librarian and math tutors from these retirees. We have a symbiotic nature in our existence between the young and old of the community.”

The school is indeed community supported. Almost all personnel are volunteers. The only people on the payroll are the teachers. Teachers have to handle disciplinary issues and do things that a team of principals, administrators and others often handle in larger educational settings.

Of the classroom environment’s effect on attending Outer Banks children, Meghan says, “The kids become like brothers and sisters. They drive each other crazy and at the same time really do grow to love each other.”

This is a childhood most adults of today wish they could have had, or could return to. Most of us likely believe it is a childhood which no longer exists. It does indeed exist, in this little community known for its wild horses and red brick lighthouse. No doubt, the original lightkeepers who maintained the light and built the schoolhouse for their children would be proud of what the entire property has become today and how it flourishes, all under the watchful energy of Meghan Agresto, modern keeper of the Currituck Beach Light.